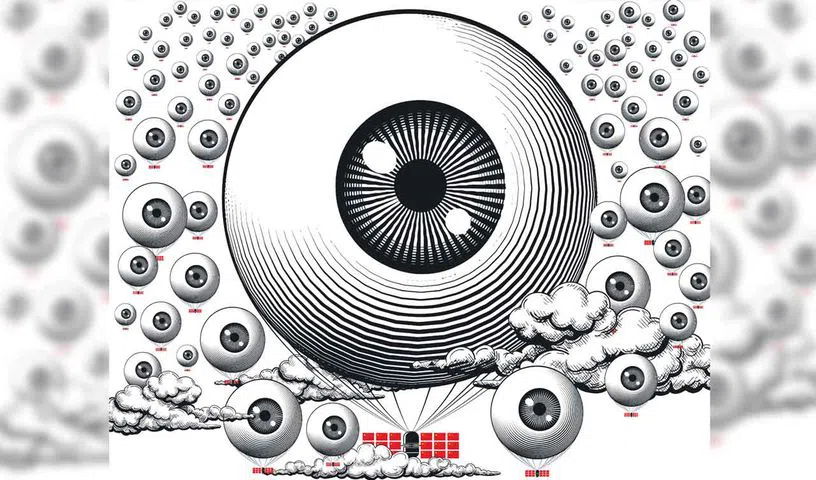

Rewind: Spy in the sky

The downing of a Chinese spy balloon by the US has put the spotlight on surveillance from the skies

Hyderabad: The Chinese balloon that traversed the United States before being shot down off the coast of South Carolina captivated public attention and drew sharp denunciations as a brazen spying effort.

After the February 4 incident, spy balloons have suddenly filled the skies. Taiwan’s Defence Ministry said a Chinese weather balloon landed on one of its outlying islands, amid US accusations that such craft have been dispatched worldwide to spy on Washington and its allies. The islet where it was found, Tungyin, is part of the Matsu island ground lying just off the coast of China’s Fujian province.

Taiwan maintained control of the islands after the sides split in 1949 amid civil war and they are considered a first line of defence should China make good on its threats to bring Taiwan under its control by force if necessary.

On February 14, Japan’s Defence Ministry said at least three flying objects spotted in Japanese airspace since 2019 were strongly believed to have been Chinese spy balloons. It said it has protested and requested explanations from Beijing. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau ‘ordered’ a US fighter jet to shoot down an “unidentified object” that was flying high over the Yukon.

But if the vehicle for espionage seemed novel, the concept was anything but new. US officials say the Chinese government has been targeting US industry and government agencies with spy operations designed to collect troves of commercial secrets and sensitive personal data — to give the global superpower a competitive edge.

“There’s a long history of spying on each other. There’s a dance and a game that both sides do. In this particular instance, maybe the Chinese got their hands caught in the cookie jar,” says Bonnie Glaser, an Asia expert and managing director of the German Marshall Fund’s Indo-Pacific programme.

China’s not the only country the US is concerned about, of course, but its efforts to penetrate American networks often seem more covert than noisy — in contrast, say, to the Russian hack-and-dump of Democratic emails before the 2016 presidential election. And its use of cyber spying to steal industry trade secrets, US officials say, runs afoul of traditional espionage norms.

China insists the balloon was just an errant civilian airship used mainly for meteorological research that went off course due to winds and had only limited “self-steering” capabilities. While it at first expressed regret over the incident, it has toughened its rhetoric and also issued a threat of “further actions.”

Tension brewing, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken canceled a weekend trip to China that was aimed at dialing down tensions. The Pentagon says the balloon, which was carrying sensors and surveillance equipment, was maneuverable and showed it could change course. It loitered over sensitive areas of Montana where nuclear warheads are siloed, leading the military to take actions to prevent it from collecting intelligence.

The Trump administration in 2018 developed a programme known as the ‘China Initiative’ aimed at cracking down on espionage operations, but it was rebranded last year following a months-long review in response to complaints that the programme chilled academic collaboration and contributed to anti-Asian bias.

Have a History

Spy balloons aren’t new — primitive ones date back centuries, but they came into greater use in World War II. During World War II, Japan launched thousands of hydrogen balloons carrying bombs, (known in Japanese as ‘Fu-Go’) and hundreds ended up in the US and Canada. Most were ineffective, but one was lethal. In May 1945, six civilians died when they found one of the balloons on the ground in Oregon, and it exploded.

In the aftermath of the war, America’s own balloon effort ignited the alien stories and lore linked to Roswell, New Mexico. According to military research documents and studies, the US began using giant trains of balloons and sensors that were strung together and stretched more than 600 feet as part of an early effort to detect Soviet missile launches during the post-World War II era. They called it Project Mogul.

One of the balloon trains crash-landed at the Roswell Army Airfield in 1947, and Air Force personnel who were not aware of the programme found debris. The unusual experimental equipment made it difficult to identify, leaving the airmen with unanswered questions that over time — aided by UFO enthusiasts — took on a life of their own.

The next major military use of balloons came during the Cold War, when the US project Moby Dick led to hundreds of balloons being sent to spy over the Soviet Union. But it was French engineer Jean-Marie-Joseph Coutelle (of the French Aerostatic Corps) who first demonstrated the potential of using a balloon to observe an enemy’s positions.

International Law

The international law is clear with respect to the use of these balloons over other countries’ airspace. Every country has complete sovereignty and control over its waters extending 12 nautical miles (about 22 km) from its land territory. Every country likewise has “complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory” under international conventions. This means each country controls all access to its airspace, which includes both commercial and government aircraft.

But the upper limit of sovereign airspace is unsettled in international law. In practice, it generally extends to the maximum height at which commercial and military aircraft operate, which is around 45,000 feet (about 13.7 km). The supersonic Concorde jet, however, operated at 60,000 feet (over 18 km). The Chinese balloon was also reported to be operating at a distance of 60,000 feet.

International law does not extend to the distance at which satellites operate, which is traditionally seen as falling within the realm of space law.

There are international legal frameworks in place that allow for permission to be sought to enter a country’s airspace, such as the 1944 Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation. The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), the United Nations agency that regulates global civil aviation, has set an additional layer of rules on airspace access, including for hot air balloons, but it does not regulate military activities.

The United States also has its own “air defense identification zone” (ADIZ), a legacy of the Cold War. It requires all aircraft entering U.S. airspace to identify themselves. Canada has its own complementary zone. During the height of Cold War tensions, the US would routinely scramble fighter jets in response to unauthorized Soviet incursions into the US ADIZ, especially in the Arctic.

Many other countries and regions have similar air defence identification zones, including China, Japan, and Taiwan.

Balloon versus Airships

China called it a “civilian airship” with “limited self-steering capability” used “for research, mainly meteorological, purposes.” But, Pentagon noted the object was a “manoeuvrable Chinese surveillance balloon” with a “broad array of capabilities” that forms part of a Chinese fleet of balloons developed to conduct surveillance operations.

Balloons and airships are both considered aircraft under international law. Airships are more manoeuvrable than balloons, which are wind-propelled. Even Chinese regulators define an airship as an “engine-propelled, lighter-than-air, manoeuvrable aircraft.”

The ICAO describes a balloon as a “non-power-driven, unmanned, lighter-than-air aircraft in free flight,” and says that an airship must give way to balloons precisely because an airship is more manoeuvrable. The organisation’s 1944 Chicago Convention provides that “every state has complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory.” Any aircraft, regardless of whether it is a commercial airliner, balloon or airship, cannot fly over the territory of another country without permission.

US President Joe Biden had repeated the legal justification cited for the downings — that the objects flying between 20,000 and 40,000 feet posed a remote risk to civilian planes. The downing of the Chinese surveillance craft was the first known peacetime shootdown of an unauthorised object in US airspace.

The manufacturer of the balloon is reportedly a research and design institute affiliated with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, and China reportedly has a growing interest in using balloon technology for military purposes.

Despite their size and vulnerability, aerostats like this offer advantages over satellites and manned aircraft. They are slow and can persist over a target for far longer than a satellite that passes over at orbital speed. Flying at just 60,000 feet (12 miles or 20 km), their cameras can achieve higher resolution than those based in orbit at 100 miles (160 km).

They are also cheaper than satellites, drones or manned aircraft, can deploy large payloads, and present a less overtly aggressive face. Indeed, they offer the possibility of a degree of plausible deniability – who would be threatened by a mere hot air weather balloon?

According to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST) — that forms the basis of international space law, space is the “province of all mankind.” OST’s Article II says: “Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”

There are 112 countries party to the OST, including China and the US, and another 23 countries that have signed but not ratified it. Because of the differing laws of physics, the line where airspace ends and outer space begins is generally defined as about 100 kilometers (some 62 miles, or 328,000 feet).