How heatwaves are hitting new highs across states

Since 1970, there have been only two years when the annual average exceeded 200 for the number of cumulative heatwave days and both have come within the last 15 years. There were 203 heatwave days in the country in 2022 – the figure represents the sum of average heatwave days recorded by the states – while 2010 had seen 256 such days, according to IMD.

The decadal average for total heatwave days zoomed to 130 for the 2010s, up by more than 35% over the previous high of 96 in the 1970s. Heatwave days in the first three years of the 2020s have already produced an yearly average of 93, the third highest since the 1970s.

Analysis of IMD data shows that compared with the previous decades, starting with the 1970s, the period 2010-2019 brought big jumps in annual average heatwave days for most states in the north-western, central and eastern and coastal regions of the country.

100315887

Withering Highs

Average temperatures over India increased by around 0. 7°C during 1901-2018 with sea-surface temperatures in the tropical Indian Ocean going up by 1°C for 1951-2015, the Centre says. The average annual frequency of warm days and nights in India has increased and of cold days and nights has decreased since 1951.

Already, 2022 was the fifth hottest year for India since 1901, when IMD started keeping records, and the outlook for El Nino weather conditions – linked with more intense heatwaves – poses worries for the country in 2023.

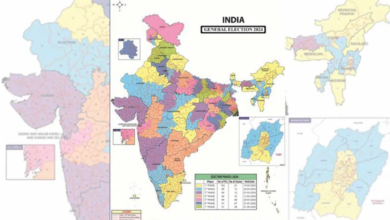

Maximum temperatures of at least 40°C or more for plains and 30°C or more for hilly regions are taken into account for declaring a heatwave. In coastal regions, a departure of 4. 5°C or more from normal can trigger an alert if the actual maximum is 37°C or more. But experts say humidity and radiation, etc. should also be factored in while estimating the severity of a heatwave. By that yardstick, The Economist magazine reports, there are parts of India where temperatures have routinely “felt like” 50°C or more in the last few decades (see map).

How Prepared Is India?

After 2030, 160-200 million Indians could be exposed to extreme heat every year, the World Bank says. An IIT-Gandhinagar study predictsthat severe heatwaves could be 30 times more frequent by 2100. If climate change continues unabated under the current policies, heatwaves could be 75 times more frequent by 2100.

A study by the Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research (CPR) found most Heat Action Plans (HAPs) – laying down guidelines for dealing with extreme heatevents – are insufficient. Analysing 37 HAPs across 18 states, CPR found that most plans do not account for local conditions and instead have an “oversimplified” approach that focuses only on extreme dry heat.

Only 10 of the 37 HAPs have temperature thresholds specific to their regions that account for localised factors, like humidity and hot nights, when declaring a heatwave. Almost every HAP fails to identify and target vulnerable populations, making it difficult to direct policy and resources towards those who need them the most. Moreover, HAPs are underfundedwith many requiring government agencies to self-allocate resources for the programme. The government estimates that between 1990 and 2020, nearly 26,000 people died due to heatwaves, though experts say the true toll is likely to be much higher. A 2022 report by medical journal The Lancet says India saw a 55% increase in extreme heat-related deaths between 2000-04 and 2017-21.

The Economic Cost Of Extreme Heat

In 2017, 50% of India’s GDP and 75% of its workforce relied on heat-exposed work. By 2030, though heat-exposed work will dip to 40% of the GDP, India will lose 2. 5-4. 5% of its GDP, or $150 billion to $250 billion, due to heat.

Extreme heat can be particularly devastating for agriculture. Heatwaves can damage crops, strain water resources, and lower the output of animal products like milk and meat. The Indian Institute of Horticulture said some regions could lose 10% to 30% of their fruit and vegetable crops due to heat this year.

Heatwaves will also likely strain the energy sector by increasing the demand for cooling. However, coal – which provides a big chunk of power in India and is one of the biggest sources of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide – stands to further exacerbate climate change induced extreme weather events.